The value of a standard house has increased from $1,000 in 1903 to more than $1 million in 2023. Reflecting on Collingwood’s recreational, real estate and economic triumphs and tribulations across the last 140-years makes an intriguing Case Study.

Many of us have enjoyed the jokes about its residents missing half their teeth, but one must give credit where credit is due. Along with being the spiritual home of the most supported team in this country, the inner-Melbourne suburb of Collingwood is one of Australia’s most iconic working-class communities.

There are many valuable lessons for all to learn from reflecting on its past.

Having studied Australian real estate history, I’ve unpacked what conditions were like through the lens of a Collingwood resident.

At the start of the century

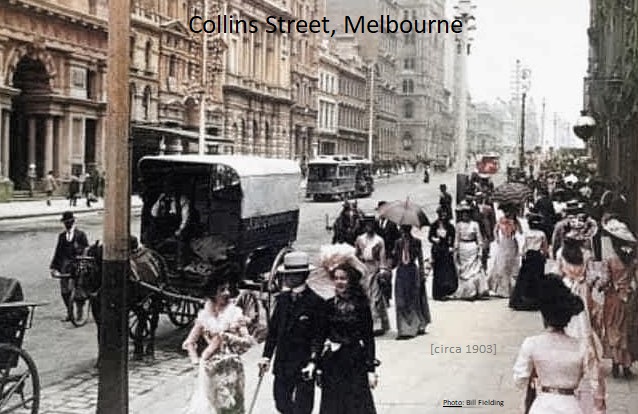

It is the year 1903, just 2-years after the Federation of Australia brought together six separately ruled colonies.

Melbourne’s population is 470,000.

You live in a standard 3-bedroom timber house, situated on a 148m2 suburban block in blue-collar Collingwood. Its value has tripled over the last 20-years to now be worth $1,000.

Your abode is equipped with an outdoor dunny, a wood stove for cooking and heating, and you receive daily deliveries of block-ice that you drop into a timber chest to cool and store your food.

Your local football club just became back-to-back VFL premiers – Collingwood defeated Fitzroy in a 2-point cliffhanger.

The economy has rebounded well from a series of bank collapses during the last decade.

Businesses across most sectors are enjoying good conditions.

As with all good democratic communities, your daily life is supported by a free market for the supply of all goods and services, including real estate.

There is significant investment in urban development occurring across your home city and strong overseas migration.

By 1910, sewerage has recently been connected to most real estate in Collingwood, including your own home.

Despite a record-high 15,000 new homes being built in Melbourne over the last 5-years (ending 1911), this supply is well short of demand.

And rental supply is particularly tight.

This is an era wherein the ratio of owner-occupier households to tenants is 50/50.

‘Back then (and always), not everyone is either ready to own their home or have implemented the appropriate choices to put themselves in a position to buy one.’

Your friends next-door, John and Jenny, are renting their home.

Plenty of other tenants aren’t as fortunate as your neighbour. Flats, hotels and boarding houses are full to the gills.

Over the 9-year period between Census surveys, Melbourne’s population has increased by 70,000 while the volume of houses ‘vacant’ declined from 2,314 in 1901 to 1,162 in 1910 (a trend that is consistent for much of Australia during the 15-years prior to WW1).

Some of your work colleagues are actively looking for rental accommodation and have shared stories of how the competition for properties keeps pushing rent prices higher.

This dynamic is the same for other commodities such as food and building materials.

On 3 January 1912, over a quiet beer with John on your front porch, you discussed a story in the Australian Town and Country Journal wherein a symptom-focused politician is suggesting the introduction of nonsensical legislation to freeze the price of rents.

“…Instead of decreasing rent, the mere proposal of the government to interfere arbitrarily between landlord and tenant would scare the capitalist from investing in house property, building would cease, and the scramble of would-be tenants for vacant houses would become even more intense….”

Your brother, Bob, has stumped up some of his own hard-earned money and taken on the risk associated with investing in real estate.

The meat-and-potatoes house that Bob added to the rental pool currently receives an 11 percent rental yield. Once expenses such as municipality rates, insurance, maintenance and management fees are added to his 7 percent interest expense, it’s slightly better than a break-even cash flow.

The release of official government statistics in a story in The Mail on 9 January 1915 confirms the price to rent a house in Melbourne has increased by 49 percent over the 13-years to 1913.

Bigger rent increases occurred in Adelaide (78 percent) and Brisbane (77 percent), while Sydney (45 percent) and various regional townships also saw high increases.

When World War 1 started in July 1914, rental supply was very tight everywhere across Australia.

Unavoidable halt to rental supply

Over the next 4-years (1914-18), 40 percent of Australia’s male population aged 18 to 44 are abroad, fighting to protect our country.

So, with unavoidable wartime restraints on household incomes, a national freeze is placed on rent prices.

The absence of skilled labour has (also unavoidably) brought the construction sector to a halt.

In 1917, with a large portion of Victoria’s farmers still fighting in the war, a significant drought over the last 2-years has restricted food supply.

The war eventually ends in 1918 with Melbourne’s population at 700,000.

In that same year, South Melbourne defeated Collingwood in the battle for the VFL premiership.

Very few new homes were built during the war years, yet Australia’s population expanded by 330,000 to 5.3 million people.

And the return of military personnel has turned the already very tight supply of housing into an instant (all-time) crisis.

With vacancy rates across Australia at zero, rental supply is so tight that home-sharing is common.

Every day, the ‘classified’ section of newspapers contain advertisements from hardworking folk desperately pleading for a spare room to rent.

Your brother, Bob, has just shared with you his frustrations as a supplier of rental accommodation. The rent controls that were brought in for unique wartime conditions are still in force. So, despite the dire housing shortage, the income that Bob receives to rent out his asset is still legislated at the same price as it was in 1913, and his expenses are now significantly higher.

‘Whether it’s a home, a hotel or a car, any rule that diminishes basic asset controls is a rule that discourages investment in such assets (ie. supply). Consequently, those who require use of such assets thereby have fewer options to choose from, increased competition, and higher chances of missing out. Unless suppliers are properly supported, everyone will end up unhappy.’

Each state has their own initiatives for supporting returning military personnel.

In Victoria, one initiative is to (through to 1924) support approximately 7,000 soldiers who were displaced from their home while fighting in the war by offering re-settlement support via granting them pastoral land.

The federal government has also identified that a national system is essential. So, they’ve established the ‘War Service Home Scheme’ (WSHS) to build Housing Commission homes for military personnel and to provide concessional loans and home insurance.

Roaring Twenties

Despite there being very little housing available, global post-war celebrations is reflected in, among other things, an economy which has been quickly thrust into overdrive.

Demand for most goods and services is very strong, including the business which you work for.

Household wages are rising. People are working longer days.

There’s a big influx of overseas migrants to fill labour market gaps, including to help build lots of new homes.

The supply (and price) of building materials, along with the generally high demand for housing has pushed asset values higher, including your own Collingwood home which is now worth more than 4-times the $300 that you paid for it.

But, for anyone with the capacity to invest in the provision of rental accommodation, rental yields are diminishing.

In December 1920, the announcement by the Victorian government to raise rents to a price that represents 30 percent more than where they were when the war started 6-years ago has been met by threats of public protests and strikes by groups of unionists and socialists.

Aside from that, the very positive post-war energy within the community is fast becoming the catalyst for a ‘Roaring Twenties’ cultural evolution consisting of jazz, dancing, art deco and theatres.

In 1925, Melbourne’s property market is still strong.

Victoria’s earlier removal of rent controls is supporting much needed extra housing supply and there are early signs of Melbourne’s rental market returning to a balanced status.

Unfortunately, it’s a very different situation in many other Australian states where rent controls are still in place.

Despite every other industry sector enjoying strong revenue growth, those who provide rental accommodation are singled out and deprived of operating in a free market.

You gain a touch of appreciation for the consequences of legislative restraints on rental supply through a conversation with a friend. He and his family are keen to accept a career advancement opportunity in Brisbane but are concerned they may have to forego it due to a major shortage of rental homes.

This situation is summed up in a story in the Wickepin Argus on 19 February 1925. It reports “…investors are not prepared to speculate in buildings to rent under the present system…there is a tremendous shortage of houses to rent in Brisbane and surrounding suburbs….until this Act is repealed, there is little hope of conditions becoming more favourable to those in search of a house.”

In 1926, your Collingwood house now has a (albeit primitive) telephone. Electricity has recently been connected to your home. And Melbourne’s CBD building height limit is now 9-storeys.

You’ve recently started commuting to your new job via a new tramline which now connects Melbourne to a ‘small town’ called Box Hill, located 14 kilometres east of the city.

1 in 2 households now own an automobile, including John and Jenny who recently purchased a new Ford, manufactured at the factory that recently opened in Geelong [From rags to riches and real estate booms].

Your life is great in 1928.

Your wage keeps increasing and Collingwood has just defeated Richmond to win another VFL premiership. Your favourite player, Gordon Coventry, is the competition’s leading goal kicker.

Primary producers are enjoying a wool (and grain) boom.

None of that helps the rental market, though.

Construction costs keep rising and most states still have the wartime rent controls in place.

‘Any lease agreement which contains T&C’s that afford the user greater control than the owner, is not a lease at all. If the user wants control, they should buy their own asset.’

Rental yields for a new investor have slipped to circa 9 percent. Once 7 percent interest and other holding expenses are deducted, the cash flow return is in negative territory.

The worst ever

It has taken a couple of years for the 1929 Wall Street stock market crash to fully ripple through to Australia.

By 1931, the grip of the Great Depression is now so strong that 1 in 3 households (including yourself) are without work.

Melbourne’s unemployment rate is 30 percent and very little money is filtering through the community.

Several banks have collapsed.

Suburbs such as Collingwood, Carlton and Richmond now resemble slums. The streets are littered with crime, disease and derelict dwellings.

As the rot sets in, many Melburnians have chosen to pursue opportunities elsewhere and have relocated to different parts of Victoria and interstate.

Key to keeping your own spirits up during this period of unprecedented poverty is inspiration gained through legendary sporting successes such as Don Bradman (the 1932 Bodyline cricket series), Phar Lap (horse racing) and Haydn Bunton (Fitzroy AFL).

Rental vacancy rates are still at zero, but many tenants have very little income to pay rent.

Some tenants have no choice other than switch to a home-share situation with friends or family.

Just as many landlords are in the same situation.

There are no winners.

By 1932, rent prices have declined by approximately 30 percent and are now at a similar price to 1925.

Rents remain at this level for a few years until, progressively, employment opportunities improve through to the late 1930s.

While the depressed economy placed downward pressure on rent prices during the 1930s, conditions were not conducive to support the much-needed investment to increase the size of the rental pool.

Verandas, sheds, wagons and tents have therefore become make-do shelter for many.

Things happen in 3’s

The agriculture industry provides 1 in 3 jobs nationally. But, in 1937, a significant drought has dealt Victoria’s economy yet another blow.

Most other industries have recovered reasonably well from the Great Depression by 1938.

Australia’s population has just ticked over to 7 million (including 1 million in Melbourne).

Your Collingwood house lost approximately 10 percent of its value over the last decade and is now worth $1,800.

Then, just as Spring 1939 kicks off, you’re listening to the wireless with John and Jenny and news breaks that Germany has invaded Poland. A political commitment from England and France sees it join forces with Poland. World War 2 has now began.

For the first few years of WW2, Australia was not greatly affected; the economy was quite stable.

But the lack of investment in rental accommodation which dates back to circa 1905 still has not been overcome.

Nonetheless, the Federal Government has moved swiftly to (again) police rent prices during war times by introducing a law which empowers each state to establish a Fair Rent Board.

Each state will now appoint a Magistrate who will determine the ‘fair rent price’, effectively freezing rent prices for the entire 6-years of the war (1939-45).

Many countries around the world introduced their own version of rent controls during wartime.

The return to a free market occurred in different years for different countries. Those who were the slowest to return created the biggest imbalance between rental supply and rental demand.

Communist Russia, for example, had very tight rent controls until (eventually) returning to a free market in the 1990s. While rent prices were kept low (rent in 1960 was approximately 5 percent of the tenant’s income), the disincentive to invest produced such a shortage of accommodation that waiting lists were up to 20-years.

Sweden commenced rent controls in 1942 and they are still in place today. The waiting list to rent an apartment is now between 11 and 30 years. Good luck with that.

‘Populate or perish’

1 million Australians served their country during the 6-years to 1945.

It is widely acknowledged that, with only 7.5 million living on it, the huge mass of ‘Land Down Under’, will be extremely vulnerable in future wars.

Hence, the introduction of a ‘Populate or Perish’ overseas migration policy, which includes a very clever marketing strategy to entice 100,000’s of English and European migrants (the 10-pound Poms).

The return of soldiers has produced positivity. You’re enjoying the confidence in the community and the aspirational spirit.

Households have discovered a strong urge to get on with building a good future for themselves.

During the initial post-war years, there has been approximately 25,000 marriages per year in Victoria.

Although any newlywed that requires rental accommodation has a significant challenge trying to find a home.

You are aware of lots of stories of more than 10-people squeezing into one small rental house and of soldiers living in tents.

The Federal Government is now distancing itself from rent controls, returning full power to the states.

Unfortunately, instead of focusing on initiatives to increase rental supply, a bigger priority of state governments now seems to be whether the Feds will continue to pay subsidies to the states to cover the cost of significant wage expenses for public servants to administer their own Rent Controls.

Even if one is prepared to invest in an asset which is wrapped up in onerous legislation and has its income-earning potential capped, rental yields have fallen even further to circa 7 percent, meaning annual revenue losses.

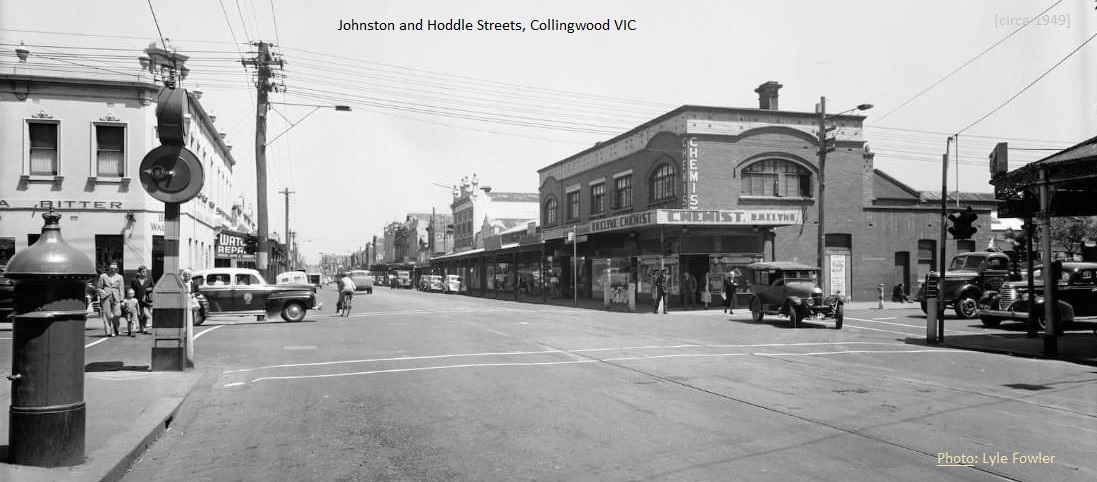

By 1948, state governments now have a system which requires landlords to have rent prices assessed by filling in a form and sending it via snail-mail to a team of public servants, who will use a bureaucratic process to come up with a (restricted) rent price for each individual rented property.

It is efficiency and fairness at its worst!

Your good friends next door, John and Jenny, have just informed you of the news that their landlord has sold the house that they rent. You are all concerned for where they’ll soon live.

SUBSCRIBE to Propertyology’s eNews

Find out more about how to navigate the Australian property market with insights from Australia’s best buyer’s agent and property market analyst by filling out the form below:

Despite the rental market now being in its 4th decade of crisis, the Australian economy is thriving.

High migration levels continue to drive national population growth of more than 200,000 per year and lots of new jobs have been created.

Your own wage has increased significantly. Property markets are booming.

Even though half of the 1940’s involved the war, your humble abode in Collingwood doubled in value during the decade.

Your brother, Bob, now has 3 single men each renting a bedroom of his modest Melbourne rental property.

But the rental income is well short of covering Bob’s costs to keep the property, so has not been able to afford to maintain it as well as he once did.

Bob is uncomfortable with the poorer quality living standards that his tenants now have, and he has mentioned to you that he is seriously considering selling.

The irony is that the collection of policies across the last 4-decades that were put in place to ‘protect tenants’ clearly had not made housing any more affordable for them to buy.

Over the 7-years directly after the completion of WW2, house values across large parts of Australia have increased by 60 percent or more.

Your own inner-Melbourne house is now worth $3,500 and a comparable house in Sydney is worth $4,500.

This story in the Sunday Telegraph on 15 January 1950 depicts a growing number of people complaining that homeownership is either beyond their reach or is less financially attractive than renting.

With Melbourne’s population now at 1.5 million in 1953, you enjoy witnessing Collingwood win their 12th VFL premiership.

In 1954, 50 percent of households now own a car and people are getting a real buzz out of going on adventure holidays to different corners of the country.

Motels and caravan parks are in high demand.

And Australia’s first ever drive-in theatre has just opened 20-kilometres east of your home, in the suburb of Burwood.

10-years on from the end of WW2, every Australian state except Western Australia still has rent controls in place.

The average price to rent a home in Melbourne now is only 4 percent more than when the war ended, and only 20 percent more than in 1925.

Bob admits to you that, while he has enjoyed the capital growth on his investment property, he’s had enough of the restrictions and has decided to sell.

But another set of legislation means that Bob cannot evict his tenant. So, he can only sell his asset to a buyer who is another investor.

The thing is, given the property is now worth a lot more than when he purchased it, a new buyer will need a much bigger mortgage than what Bob has. The low rental returns makes it an even less attractive proposition to anyone else. Meaning, Bob is boxed into a corner where he literally is unable to sell his asset.

‘The term ‘NO CAUSE’ is nothing more than ‘NON-SENSE’. Let’s be crystal clear, the expiry date for a tenant’s lawful use of an asset is determined when they first enter the lease. In most cases, the asset owner will be happy to offer the tenant another lease term. But it is the owner’s right to say ‘no’ without any obligation to give a reason why. The sacrifices made to buy the asset gave them that right.’

Over the next couple of years, your home city plays host to the Olympic Games (1956) and Collingwood win their 13th VFL premiership (1958).

The property market has continued to boom throughout the entire 1950’s, adding a further 110 percent capital growth to your Collingwood house and increasing its value to $7,500.

But decades of rent controls have eroded rental returns such that rental yields are now 6 percent.

The eventual return to a free market

By 1960, property investing is still an environment that very few investors have the confidence to place their hard-earned capital into.

While many have the equity and financial capacity to invest in their future, history will go on to reflect that a low appetite to invest will leave a most unwanted legacy wherein 2-generations end up dependent on modest aged pensions, redirecting important taxpayer funds away from infrastructure spending.

The insufficient size of the rental pool means a continuation of poorly maintained rental homes, last-resort home-sharing and lots of other makeshift living arrangements.

A letter to the Editor of the Canberra Times confirms the price to rent a 2-bedroom brick house is now much the same in 1961 as it was 34-years earlier, in 1927.

Meanwhile, there has been no price-setting limitations on the provision of all other goods and services. And household wages are now significantly higher than when the craziness started all those decades ago.

Globally, a dire shortage of rental accommodation is a common theme through to the late 1960s.

‘Economist from all over the world subsequently conducted (reflective) studies on the impact of rent controls and tenancy regulations. They concluded that restrictions had adverse effects on both new housing construction activity and investment in rental accommodation.’

Unfortunately, things aren’t any rosier for you on the footy front. Throughout the 1960’s and 1970’s, Collingwood lost the VFL Grand Final 8-times and by narrow margins, earning the tag ‘colliwobbles’.

In 1966, when Australia introduced decimal currency, a few state governments had (finally) come to their senses and accepted that the only way to eventually return to a balanced rental market was to restore free market conditions.

It was not until the early 1970’s that sanity prevailed in all Australian states.

Today

While it’s seen a few different coats of paint and some cosmetic improvements, that modest, 3-bedroom timber house is still standing today on the same 148m2 block of land.

Subsequent to 1970, it has withstood Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, a couple of serious oil crisis, 4x national recessions, more natural disasters, a global financial crisis and a global health pandemic.

That same Collingwood home is now worth more than $1 million.

Collingwood has undergone significant urban renewal, although it has retained its blue-collar charm.

And it will always be home to one of Australia’s most respected sporting teams.

Results from the 2021 Census say that Collingwood homes have an average of 1.9 people living in them and the median household age is 33.

These days, most Collingwood households bring in 2-incomes.

64 percent of Collingwood households still depend on rental accommodation.

Nationally, 1 in every 3 households rent.

And the total size of the rental pool is circa 3.3 million dwellings.

While creating decades of carnage from their (many) poor housing policies, the collective state and federal governments have only managed to fund 8 percent of the rental pool.

‘One constant that has remained throughout the last 200-years is that, when it comes to properly understanding the intricacies of housing supply and demand, politicians and their various related departments have always been as ‘useful’ as gumboots on pelicans.’

The other 92 percent of rental homes in this country have been funded by 2.2 million private citizens. These people prioritise financial independence, have demonstrated a preparedness to exercise financial discipline, and have taken educated risks in pursuit of achieving their goal.

According to statistics from the ATO, 90 percent of these everyday Aussies have taxable incomes of $100,000 or less.

We can now only hope that one of the most valuable lessons that is taken from the past is the importance of supporting (as opposed to restricting) those who have an appetite to invest in the provision of rental accommodation.

Propertyology are national buyer’s agents and Australia’s premier property market analyst. Every capital city and every non-capital city, Propertyology analyse fundamentals in every market, every day. We use this valuable research to help everyday Aussies to invest in strategically-chosen locations (literally) all over Australia. Like to know more? Contact us here.